Until the time of this commission, Ed Lippmann’s work was synonymous with steel framed rectilinear architecture. This house, daubed the ‘Butterfly House’, challenged Lippmann to explore more organic curvaceous forms in a language of concrete and masonry. The adventurous scheme, now a landmark in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, ruffled the local council’s feathers.

“The local building inspector felt that it didn’t fit in with the neighbourhood which I took as a complement,” says Lippmann, pointing out the proliferation of red brick interwar bungalows in Dover Heights at that time. Lippmann’s diametrically opposing view of the appropriateness of the design within the local context led to a court challenge, averted at the 11th hour with a subtle adjustment to the position of the house on the site. The iconic landmark was air born.

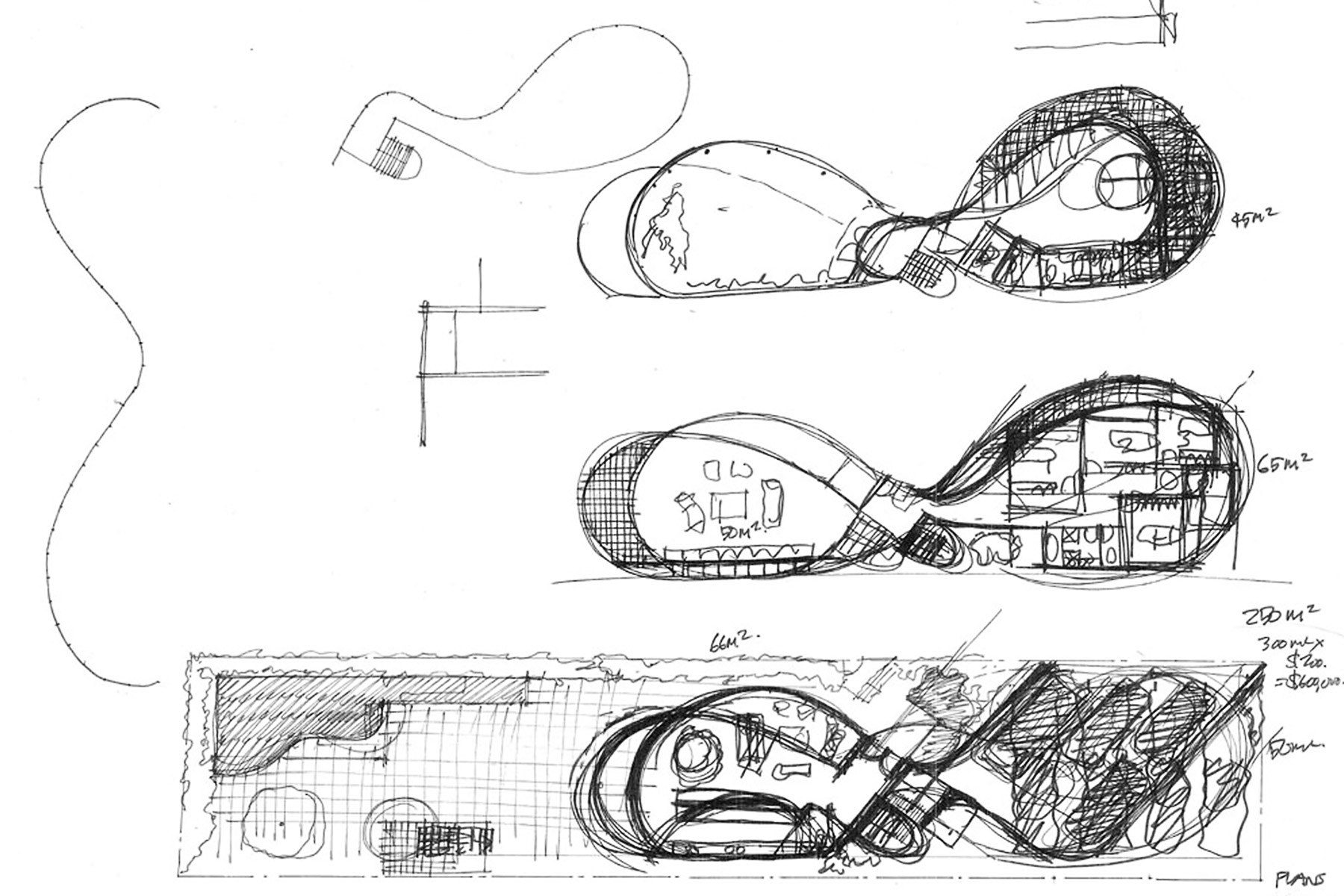

The starting point for the project came from an eccentric Malaysian property developer with one overriding requirement “a curved house conforming with Feng Shui principles, ensuring that energy or “chi” would flow through the house freely and not be trapped by square corners.” When Lippmann enquired as to the budget, the answer was succinct: “there isn’t one”.